For years, the Navajo Code Talkers’ stories and contributions were hidden from public knowledge, leaving citizens unaware of how they helped the United States win World War II.

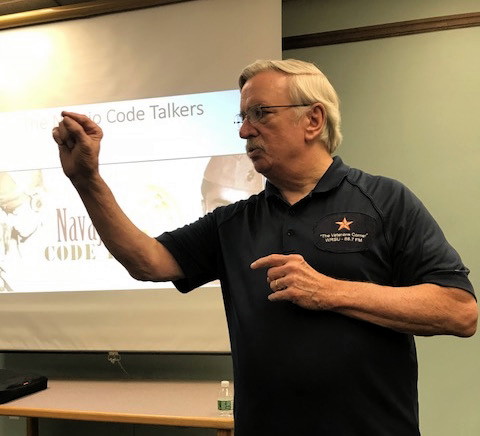

Equipped with slides and music, Rutgers University radio host Don Buzney gave a presentation about the Navajo Code Talkers and their service to America at the Spotswood Library.

Buzney is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran who worked for the Navajo Nation in Gallup, New Mexico, for two years. While there he would on occasion meet and interact with the Navajo Code Talkers.

“It is important to remember the Navajo Nation was a federally certified enclave onto itself. They were not required to serve, they were exempt from the draft [and] did not have to go,” Buzney said. “When you think about the history and the sad tragedies that were inflicted on many Native American nations, including the Navajos, it’s rather surprising that they did, but they did and they did it willingly.”

The day after the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on U.S. military ships and personnel at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered a nationwide address on Dec. 8, informing citizens that many American lives were lost, according to Buzney.

Buzney, an East Brunswick resident, said that after the devastating loss sustained by the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese saw the United States as vulnerable. The United States had eight battleships that were sunk; however, seven were refloated and returned to war.

There were dark days for the Allies in the Pacific: from December 1941 to May 1942, the United States saw an unbroken string of Japanese victories, including Wake Island, Guam, the Philippines, Singapore, the Malayan Peninsula, Hong Kong, Burma and India. When Australia’s northernmost city, Darwin, was bombed, the Japanese seemed poised to launch an invasion of Australia, Buzney said.

“The Japanese strategy was to have an influence that would stretch from Australia all the way up to the central Pacific, all the way to the Aleutian Islands,” Buzney said. “That was their tactical goal, but they had not taken into account the resurgent U.S. Navy, the resiliency of the American people, U.S. Naval Admiral Chester Nimitz, the U.S. Marine Corps and the Navajo Code Talkers.”

Buzney said the Battle of the Coral Sea took place from May 4-8, 1942. What was significant about this battle was that it was the first time in history the opposing ships never fired directly at each other, Buzney said. It was a battle fought totally by carrier-launched aircraft.

“The Battle of the Coral Sea could best be described tactically as a draw. The U.S. Navy did inflict more damage on the Japanese than they inflicted on us, but we also sustained heavy losses; [however,] strategically it was a huge victory for the U.S. Navy because it was the first time since Pearl Harbor that a Japanese invasion force had been turned back without achieving its objective,” Buzney said.

The Battle of Midway took place four weeks later from June 4-7, 1942. It was the first decisive major naval victory against the Japanese. The Japanese lost four aircraft carriers, a cruiser and 202 aircrafts, and sustained more than 2,500 casualties. The U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown, the destroyer USS Hammann and 145 aircraft, and sustained 307 casualties, according to Buzney.

For six months the United States was on the defensive, but now the tables were turned, according to Buzney.

“The Marines were tasked with the invasion of Guadalcanal, which was to take place in August 1942, but the Marines high command had a dilemma: the need for secure code. The Japanese, who were skilled code breakers, had been able to decipher every code thus far devised by the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Air Corps,” Buzney said.

“Without a secure code, military operations would be disrupted, needless lives would be lost, the enemy would know what we were going to do before we did it, which could prolong the war. Literally, victory and defeat hung in the balance,” he said.

Philip Johnston was the son of a missionary to the Navajo Nation. Johnston was raised on the Navajo reservation and he spoke Navajo fluently. Johnston believed that the Navajo language was the key to a secure code the Marines were looking for, according to Buzney.

“The Navajo language is an unwritten language with its own syntax and tonal qualities. The language has no alphabet or symbols and is spoken only on the Navajo lands of the American southwest,” Buzney said.

Johnston asked for a meeting with Marine Major General Clayton Vogel who was the commanding officer of the Fleet Marine Force.

“When [Johnston] met with Vogel, [he] was very skeptical at first because military code at the time was encrypted by high-tech black boxes,” Buzney said. “The idea of using a 1,000-year-old language was totally abandoning that technology [and] was really out of the box, but with Guadalcanal looming on the horizon, Vogel had to consider all possibilities.”

Buzney said Vogel sent a team of Marine cryptographers to Window Rock, Ariz., and once there they conducted tests under simulated battlefield conditions with the Navajos. They came away very impressed.

“The Navajo were able to code, transmit, decode and message in 60 seconds where machines at the time took at least 30 minutes. Based on these results General Vogel recommended that the Marines recruit 200 Navajos. Before the war was over, 420 more would follow,” Buzney said.

In addition to having to complete the grueling Marine Corps training, Buzney said the Navajo recruits had to devise a code, learn 260 words, and then combinations of those words. Everything was committed to memory, as nothing was written down.

“The average age of a Navajo Code Talker was 19, which means there were 17- and 18-year-olds also along with other young men in their 20s,” Buzney said. “Most had never been off the reservation before and now found themselves thrust into war in the Pacific. Again, remember, they did not have to go, but they did.”

Buzney said the code talkers served in all six Marine divisions and took part in every assault the Marines made in the Pacific from 1942-45, and their skill and bravery became legendary. The code talkers served on Guadalcanal, Tinian, Saipan, Cape Gloucester, Bougainville, Tarawa, Peleliu, Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Thirteen code talkers were killed in action, 42 were wounded, but no code talker was ever captured by the Japanese, according to Buzney.

Following the Battle of Imo Jima, Buzney said, Major Howard Connor, who was the fifth Marine division communications officer, declared that if it were not for the Navajo Code Talkers, the Marines would never have taken Imo Jima.

After World War II, Buzney said, “The code proved so successful that even after the war ended it was cloaked in total secrecy. Its existence was not even officially acknowledged by the Department of Defense until 1968 and it is notable to mention that the code talkers also served in the Marines in Korea.”

When working for the Navajo Nation, Buzney said he was also involved with the New York City Veterans Day Parade for several years. In the course of that he came to know a Vietnam combat veteran, Bill Nelson, who at the time was also the chairman and CEO of HBO.

In early 2010, HBO came out with a documentary series “Pacific” about the Marines in the Pacific. Nelson sent him an advance copy.

“It was an incredibly well-done series, but I was struck by the fact there was no mention [and] no acknowledgment of the Navajo Code Talkers,” Buzney said. “So I called [Nelson] in New York and I said, ‘That was a great series, very well done, but I don’t know how they could do a series about the Marines in the Pacific without acknowledging the Navajo Code Talkers.”

Buzney said a couple days later Nelson called him back and said the documentary should have acknowledged the code talkers.

Wanting to make it right, Buzney said he informed Nelson there were 13 code talkers, plus each code talker had a caregiver and three staff members, a total of 29. Nelson flew them all to New York courtesy of HBO, where they rode on HBO’s float at the 2009 New York City Veterans Day Parade as their guests of honor.

The next day, Nov. 10, the Marine Corps celebrated its founding and the code talkers were guests of honor onboard the Intrepid, the museum aircraft carrier docked in New York City at Pier 86.

Buzney said when they arrived at Pier 86, they were met by a phalanx of U.S. Marines in dress blues, the honor guard that escorted them to the Intrepid for the ceremony.

Asking Navajo Code Talker Keith Little why the Navajos volunteered for World War II given the history, Little said, “Well, it was our land. We were aware there was an enemy attacking our land so we had to defend it.”

“The Navajo Nation to this day on a per capita basis sends more of its young men and women to serve in America’s military than any other ethnic group in the history of the United States; that’s pretty remarkable,” Buzney said.

Buzney hosts the Veterans Corner every Wednesday from noon to 1 p.m. on Rutgers Radio WRSU-FM, 88.7.

Contact Vashti Harris at vharris@newspapermediagroup.com.