Deadly school shootings that started with Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, in 1999 forever changed the way police officers across New Jersey, and America, safeguard our school children.

Now, to help school children rebound from the emotional fallout of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, the role of today’s specially-trained school resource officers (SROs) must evolve again, says John Zebrowski, president of the New Jersey Association of Chiefs of Police (NJSACOP).

New Jersey’s 2,500 police officers, assigned to schools statewide, are “on the front lines, ready to assist youngsters returning to classrooms with post-pandemic anxiety, even fear, from 18 months of isolation while distance-learning from home,” said Zebrowski, the Sayreville police chief.

“Working with faculty at their schools, SROs are well-equipped with communication, teaching and mentoring skills to help troubled youngsters overcome reticence and trepidation about wearing masks and staying socially-distant as they re-socialize with classmates and teachers,” Zebrowski said. “We want SROs to be the key in-school resource during this difficult transition back to school.”

On behalf of the NJSACOP, Zebrowski’s call-to-action gets strong grades from SROs, other police chiefs and school administrators.

“It’s refreshing to hear. This is right in our wheelhouse,” said Patrick Kissane, executive director of the New Jersey School Resource Officers Association, who supports NJSACOP’s efforts to encourage school officials to make greater use of police officers in their primary and secondary schools.

“There’s a good chance SROs will never face an active shooter in any school. But, there’s a great chance every SRO will face kids in crisis in every school,” said Kissane, noting that post-pandemic anxiety among students and school staff “is a crisis that nobody could have predicted.”

SROs and retired police veterans – called Class III Special Law Enforcement Officers (SLEOs) – who schools hire for extra security – are required to take a state-approved 40-hour course about safety precautions, threat assessment, active shooters, counter-terrorism tactics, anti-bullying, searches and seizures, and more.

Training also strongly emphasizes ways for SROs to be positive adult role models, with a wealth of instruction about assessing behaviors and identifying at-risk kids, teaching methods, mentoring and teamwork. Curriculum updates are now underway to better prepare SROs to intercede with students who face adverse childhood experiences.

New Jersey was among the first states to enact mandatory SRO training once police officers became welcome in-school fixtures after the Columbine High School massacre and subsequent school shootings that tragically turned places like Sandy Hook Elementary School in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, in 2012; and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in 2018, into household names.

To be effective, “kids must see me as more than a cop,” said Montville Detective Scott McGowan, a four-year SRO in his town’s public schools. “Students need to see me as a husband, as someone’s father, as someone’s child, and as someone who was once a student just like them.

“Their perception helps me become another adult who they can trust and speak with candidly,” said McGowan, adding he is always mindful that “SROs are not guidance counselors, social workers or school psychologists. But we are required, when necessary, to make (those) referrals.

“Often kids just need an impartial adult to be a good listener. Lots of issues get resolved that way. They need a little informal advice from someone – not a teacher, not their parent – who already survived middle school,” McGowan said. “Having an open door, being empathetic … that’s a big part of my job.”

“SROs do far more than most people ever realize. They don’t just walk hallways waiting for something to happen,” added Police Chief Christopher Leusner, from Middle Township in Cape May County.

Many of New Jersey’s SROs instruct anti-drug and alcohol programs. They share mystery-meat cafeteria lunches with students; read to grade schoolers; mingle with pupils at bus stops; dance along with cheerleaders at pep rallies and football games; make cameo appearances in school plays; and perform in school talent shows.

“Doing what we do (as SROs) can be lots of fun, but it’s always centered on one goal: Building confidence and trust,” said McGowan, who teaches what’s become a popular Montville High School criminology course.

School officials also strongly support SROs.

“Educators, especially now, need all the help we can get,” said Brian Latwis, the Barnegat Superintendent of Schools, explaining more youngsters are returning full-time with issues that range from anxiety to “academic fatigue, because they no longer accustom to eight-hour school days.”

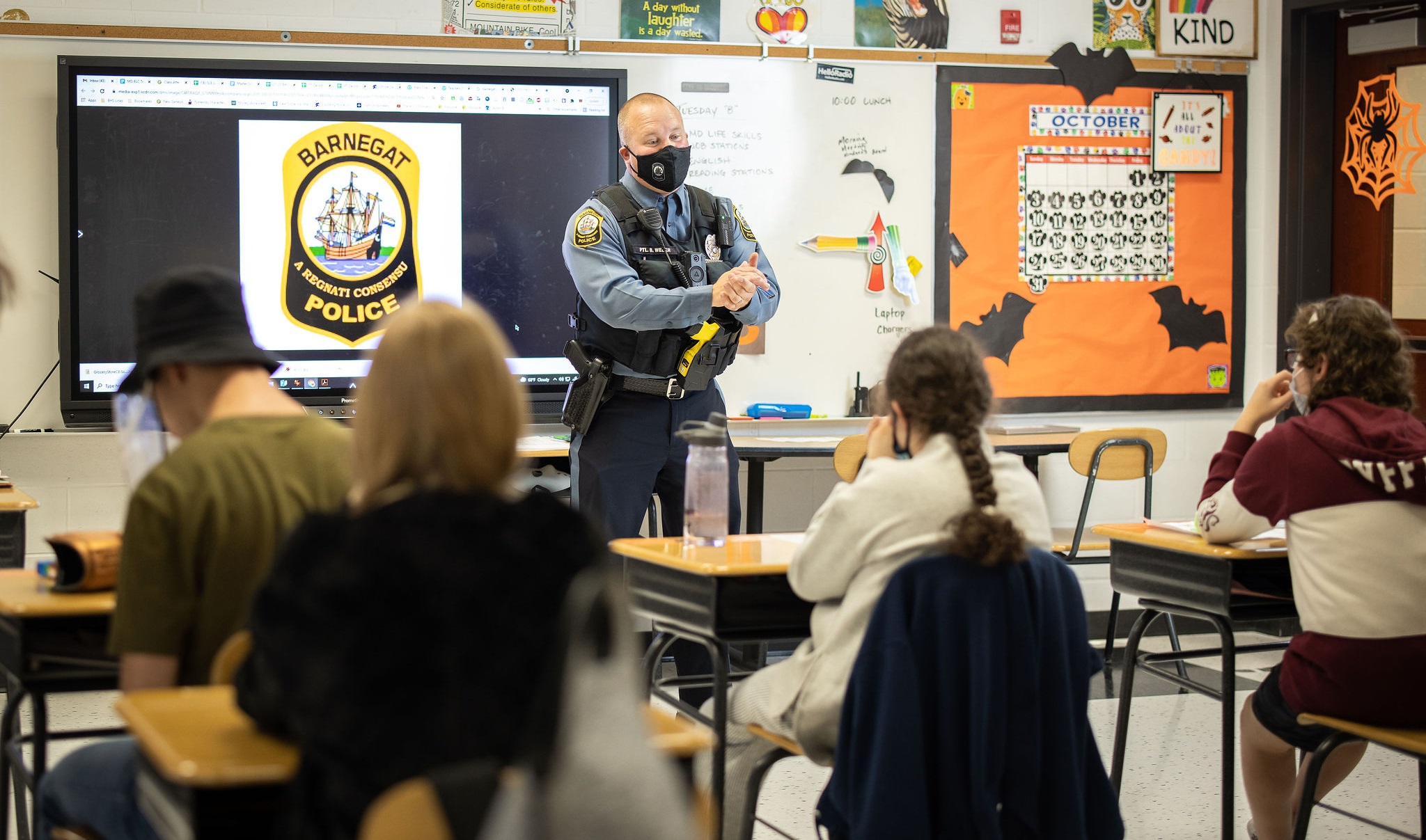

Latwis says his district’s SRO, Patrolman Brian Weber, and two Class III officers “are valuable partners with our guidance counselors and teaching staff. They really get to know our kids, that helps these officers be better mentors; relieve (student) concerns; and calmly, casually de-escalate situations.”

“Part of my job is certainly to recognize any potential (school) threats, to respond to crisis situation, and to deal with criminal activity,” said Weber, a 14-year police veteran now in his third year as Barnegat’s SRO.

“My larger role is to help students feel comfortable and earn their trust as a positive role model who genuinely cares about them,” Weber said. “Hopefully, I am also changing any misconception they may have about law enforcement and police officers.”

Weber said he notices some students are uneasy or have “other challenges” since returning to school.

“School provide kids with structure. After months of virtual learning from home, more (students) have trouble focusing in class for 50 minutes,” Weber said. “It’s not a police matter, but it’s something I talk about with them. Hopefully, I can help.”

“The strong, healthy relationships that SROs build with students has public safety benefits that reach beyond school walls,” Leusner said. “SROs also create confidence and trust with students’ families. They extend the safety net that all (police) departments provide into neighborhoods and across their communities.”

Zebrowski summed it up, saying, “Circumstances today have made school safety about more than pinpointing and preventing potential threats. The role of SROs is evolving with our times and should continue to be a vital service for our children and their families, and for schools and the public at-large.”

- This Your Turn was provided by Jaffe Communications.