Whether it was learning about a supercomputer, earthquakes or how clouds form, students and families – through hands-on activities – experienced different areas of science at the second annual “Spring Into Science.”

“Spring Into Science” returned to Princeton University’s campus inside the Frick Chemistry Laboratory building and Princeton Neuroscience Institute (PNI) on April 20.

“The biggest tweak we made [from the first year] was having more science for the kids and students in our area,” said Paryn Wallace, associate director of Science Outreach at Princeton University, adding they worked on making the event “bigger and better.”

“We have expanded and used this entire space at Frick and the space in PNI.”

In 2024, “Spring Into Science” had a significant increase in attendance and engagement following its first year with more than 700 students attending the event.

“Last year I think we had maybe about 400 students,” Wallace said. “This year I had over 700 registrations and this is just kids not the families, parents and other people that came with them.”

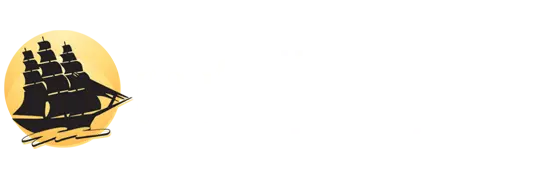

Thirty-four exhibitor tables were set up to teach and provide science activities for students from fourth grade to 10th grade along the Frick Atrium in the laboratory building,

“The goal of Science Outreach is to make sure that kids who are younger students have an experience and see the science, touch it and see the things happening, so it will increase their knowledge of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), increase the pipeline of STEM and engage learners,” Wallace explained.

Science Outreach at Princeton supports 10 academic departments – Astrophysical Sciences, Center for Statistics and Machine Learning, Chemistry, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Geosciences, Mathematics, Molecular Biology, Physics, Princeton Neuroscience Institute, and Psychology.

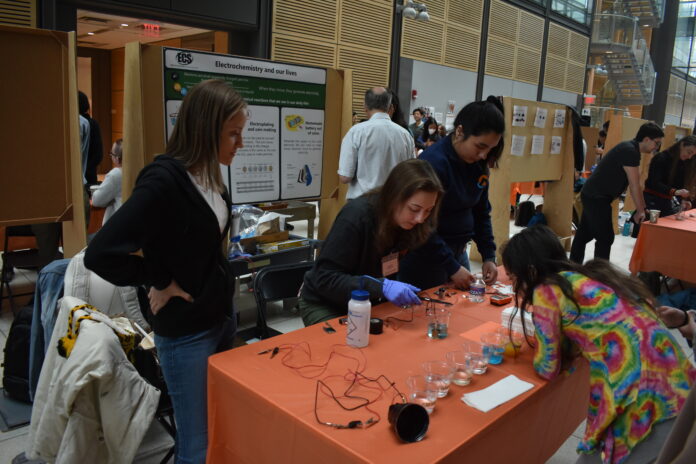

There were four live chemistry demonstrations, which featured interactions with student attendees as they answered and engaged with questions asked by the demonstrators.

Angie Miller, lecture demonstrator in the Princeton University Department of Chemistry, led a series of experiments using the scientific method to demonstrate different discoveries about the world.

In the chemistry demonstration, she showed and explained an experiment where there were three balloons on the table – one containing helium, another containing hydrogen, and a third balloon having hydrogen and oxygen.

The audience was tasked with figuring out which balloon was which. Using fire up against each balloon to pop it would determine which balloon contained helium, hydrogen, and hydrogen and oxygen.

“The helium one will not burn at all,” Miller explained. “The hydrogen one only has access to the air around us. The hydrogen and oxygen one – because I have them both together in the same balloon – it will burn a lot.”

The sounds and experiment had the audience oohing in excitement.

Another experiment featured a marshmallow figure in a transparent glass bell jar which was hooked up to a house vacuum. It showed the marshmallow expand and shrink when the air is removed from the jar.

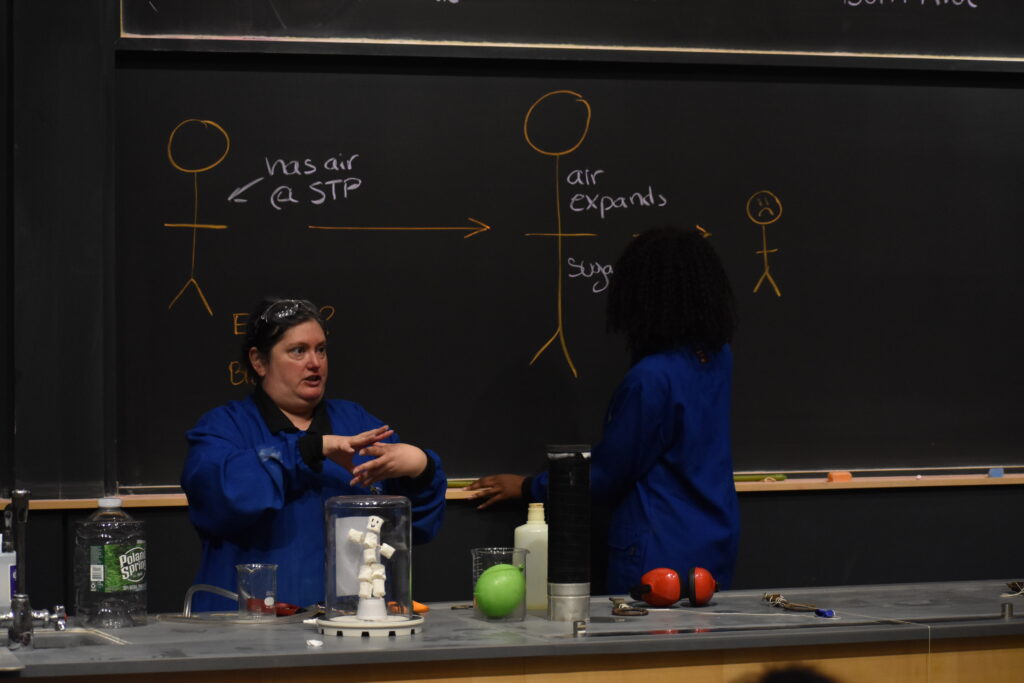

On the Frick Atrium floor, a demonstration allowed students to see how clouds formed.

“We have a container that contains water vapor from the air all around us and particles called aerosols which are also in the air, but we also add some more in by spraying deodorant,” said Michael Schroeder, a first-year PhD student in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department.

“Then as we pull on the plunge it lowers the pressure, which also lowers the temperature and then makes the temperature go lower, so the air is super saturated. The water vapor squeezes onto the aerosols already there forming a cloud.”

Schroeder said it has been great to see the students and families engage with the demonstration.

“I love seeing this enthusiasm in science,” he said. “I love being able to share what I do at an age-appropriate level.”

Another science activity demonstration illustrated rotating fluid mechanics – how people understand the atmosphere and the ocean weather patterns.

“In this weather map you see all this swirling motion, which is due to what is called the Coriolis effect, because the rotating planet we live,” said Steven Griffies, lecturer and mentor in the program of Atmospheric and Ocean Sciences within the Department of Geosciences.

“With a rotating tank of water, we can illustrate some of the same patterns that we see in the real atmosphere, whereas in the non-rotating tank, it is a very blah, boring behavior and not a lot of structure to it.”

The students were asked a simple question after putting food coloring in the non-rotating tank and food coloring in the rotating tank. Which one mixes quicker?

“A lot of them say the rotating tank because it is moving, but in fact you put food coloring in the rotating tank, it almost goes to a column and almost does not move much at all from there,” Griffies explained. “Whereas from the non-rotating tank, [the food coloring] moves out without a clearly defined shape and mixes up pretty quickly relative to the rotating one.

The Princeton Neuroscience Institute featured an escape the cell room, where students and families learned about cells and how they work.

Additionally, the space provided a room for live combustion demonstrations to take place, as well as had exhibits that taught about the parts of brain with real examples and peoples taste pathways with the tongue.

Reed Maxwell, professor of Civil Engineering and Enviornmental Engineering and the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton University, shared there are 20 graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and other staff, and undergraduate interns in the research group he leads.

They try to understand how much fresh water there is on the planet and how fast it is being depleted and how fast it is being replenished. This is their second year being part of “Spring Into Science.”

“This is a demonstration of a drone we have that we use to fly over two sites – one site is in the upper Colorado,” Maxwell said. “The upper Colorado River basin [provides] water for 40 million people. Right now, it is in crisis. It is at its lowest reservoir levels we have seen in 100 years.”

Maxwell said their hypothesis is that plants are using more water as the climate warms to stay alive.

“That water is being taken out the system,” he said. “We have an intensive field site in the upper Colorado. We fly the drone over our site and can look at vegetation dynamics and vegetation temperature which we can use to infer photosynthesis and transpiration (process where water moves through a plant and evaporates).”

Other demonstrations included a sand tank aquifer model that taught ground water flow processes – how ground water connects to rivers, how ground water can recharge, and groundwater contamination.

A third demonstration was about saltwater intrusion along coastlines – understanding how saltwater intrudes into the freshwater and can salinate coastal aquifers, Maxwell said.

“A lot of coastal aquifers like in South Jersey are used to grow food and if [it] gets too much saltwater intrusion, then the water that is pumped out of the ground is too salty to use to grow food and can contaminate drinking water.”