by Jay Watson, Co-Executive Director, New Jersey Conservation Foundation

Most longtime New Jerseyans – especially gardeners and growers – have noticed that winters have gotten milder over the last few decades. Cold weather seems to arrive later, and the Garden State gets fewer days of truly frigid, bone-chilling weather.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has noticed, too, thanks to decades of collecting temperature data at thousands of weather stations across the nation.

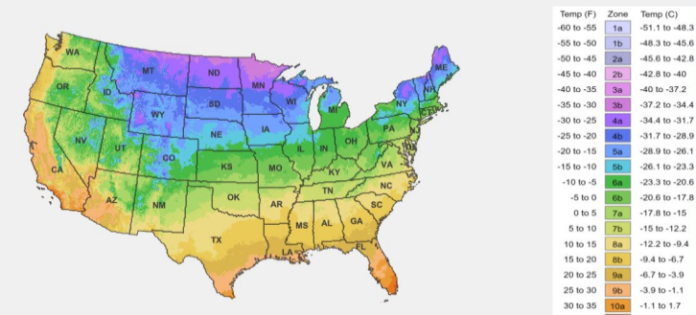

The USDA recently released an updated “Plant Hardiness Zone Map,” a resource used by an estimated 80 million gardeners and growers to determine what perennials can be planted in each region with strong odds of surviving winters. It’s the first update since 2012.

According to the new map, about half of the United States – including all of New Jersey – has shifted to a new hardiness zone due to the warming of our climate. This means changes in the plants that are able to thrive here.

Hardiness zone designations represent what’s known as the “average annual extreme minimum temperature” at any given location during a 30-year time period. The designations don’t reflect the coldest it has ever been, or ever will be – they’re simply the average of the lowest winter temperatures during the period of 1991-2020.

In total, the map includes 26 hardiness zone and half-zone designations, ranging from 1a in the coldest region of Alaska, to 13b along the balmiest parts of the Puerto Rico coast. (The higher the number, the warmer the temperature.)

New Jersey is in the middle. It contains four plant hardiness zones, and all have shifted to reflect warmer temperatures. For example, Sussex County in the north has gone from 6a to 6b, reflecting an average low temperature four degrees higher than in the 2012 map. Cape May at the state’s southern tip has moved from 7b to 8a, reflecting a three-degree temperature shift.

New Jersey’s warmer winters and hotter, longer summer droughts have many implications for gardening, agriculture and ecological restorations on damaged lands.

Low temperature during the winter is a crucial factor in the survival of plants, and the zone shift means more plants common to southern states will be able to survive here in the Garden State. Many New Jersey gardeners can now grow southern species like camellia, magnolia and crape myrtle with less danger of them being killed by winter’s cold.

On the flip side, warmer weather means that other New Jersey species that require cooler temperatures will have a harder time surviving. For example, cranberry and apple agriculture may eventually become difficult or impossible in New Jersey if heat-tolerant varieties cannot be developed, as these crops are northern and adapted to cool summers. New Jersey’s Pine Barrens is already the southernmost location in the U.S. where cranberries are grown.

New Jersey’s popular annual crops like corn, tomatoes and peppers will not be affected by milder winters, as they die at the end of each growing season and are replanted in the spring. The warming trend means that in many places they can be planted earlier in the spring without danger of frost, and can survive later into the fall. But these tropical crops will require more water during summer droughts, and may have to fight off increases in insects and disease pathogens at great expense.

A type of human intervention termed “assisted migration” northward will need to be employed in ecological restorations.

Bald cypress trees, a southern species, are now suitable for freshwater wetland restoration projects in some parts of New Jersey, as it appears they eventually will be able to reproduce here.

New Jersey’s trees and other woody plants that are also currently found far to the south whose seeds are wind-dispersed (like sweet gum) or whose seeds are carried in bird droppings (like sassafras and red cedar) would also thrive in ecological restorations, as they will have the easiest time gradually migrating northward as the climate warms.

However, assisted migration through ecological restorations is only practical on a small scale, with a few species, due to the tremendous expense.

Many New Jersey trees and plants will find it tough to adapt to a warmer climate, even in assisted migrations. For example, our state is becoming too hot for sugar maples and possibly even our state tree, the northern red oak! The many southern oak species will have difficulty migrating northward, as their acorns aren’t dispersed long distances by wind or birds. Migration through successive generations is an extremely slow process! And thousands of beneficial insect species that depend upon host plants won’t be able to expand northward if their host plants move too slowly.

As New Jersey’s ecosystems lose species due to intolerance to climate change and introduced pathogens or insects (such as ash trees in forests dying due to emerald ash borers), the overwhelming result will be these collapsing habitat types will be taken over by common, aggressive species. Weeds – both alien and native – will gain ground the fastest.

Let’s hope human societies are able to slow down the pace of climate change, because otherwise there will be a huge toll on the natural systems we know today. Controlled environments like gardens, farms, orchards and plantations will be able to survive with the help of tools like the plant hardiness zone map, but nature is on its own. Nature, as resilient as she can be, will not fare well if climate change is too rapid. Let’s do what we can now, to give it the time it will need to succeed!

To learn more about updated plant hardiness zones and view the interactive map, go to https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/. Type in your ZIP code and you can learn about the zone you live in and how it has shifted since the last plant hardiness map came out 2012.

And for information about preserving New Jersey’s land and natural resources, visit the New Jersey Conservation Foundation website at www.njconservation.org or contact me at [email protected].